Who I Am, Told by a Wooden Figurine

I was seven years old, in the first grade of School No. 1 in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. There’s no way to confuse that year with any other — it was the year the civil war began. By the time I started second grade, we were already living in Ashgabat, Turkmenistan.

I don’t remember what holiday it was — perhaps New Year’s, or something similar — only that parents were required to prepare small gifts for a random exchange among the children. I no longer recall what my mother wrapped up, but I remember what I received: a bar of chocolate. I can’t remember how the exchange was organized — whether we drew lots or the teacher simply reached into a bag — those details have vanished.

The chocolate didn’t make much of an impression. Those were considered hard times, but the Soviet Union had already collapsed, and shops were filling up with imported candy and chewing gum. It was hard to be amazed by chocolate. The only thing I remember clearly is the subtle tension — the almost thrilling anxiety — of watching my classmates: someone might have gotten something better.

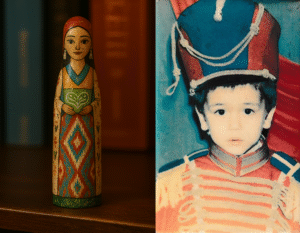

I can’t recall any names or faces — in the next three years, I would change schools three more times — but one moment has stayed with me. A girl in my class was holding a small wooden figurine of a Tajik woman in national dress. It was hand-painted, like a matryoshka, though different in shape — tall, slender, carved from a single piece of wood, and of course, unlike a matryoshka, it didn’t open.

I asked if she’d trade it for my chocolate. She agreed without hesitation. I still remember the thrill of that “successful deal” — that brief fear that the trade might fall through, that she’d change her mind at the last second. To me, it felt like a triumph: the figurine was real wood, not plastic.

More than thirty years later, I still wonder why. Why did a seven-year-old want that figurine so badly? What did I sense in it? I remember bringing it home proudly and showing it to my parents. They don’t remember it now, and the figurine itself has long since disappeared. Maybe they praised me back then — or maybe I just imagined their approval. Not for the trade itself, but for the object. It was made of wood. It was handmade.

I think that’s when I first felt the quiet reverence for things made by hand — a feeling that has stayed with me ever since. Especially when I think of my grandmother’s apartment, crowded with souvenirs from around the world.

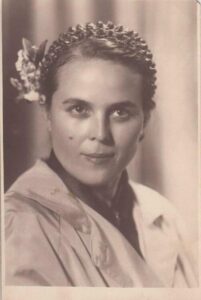

I grew up in a family where every surface of furniture was covered with figurines and trinkets. My grandmother’s home in Ashgabat — where we moved after the war began — was practically a museum. She had been a Soviet official and had traveled widely, even to countries outside the socialist bloc — the United States, Ireland, Brazil, several in Africa.

Her shelves and cabinets were full of souvenirs: carved masks from Congo, wooden giraffes, a bust of an African woman, shining plates, and nameless statuettes whose origins I can no longer trace. From America, I remember a sheriff’s badge — a little metal star I absolutely adored. It was, of course, just a souvenir, but at the time I was certain it might carry some real authority — if only I could be dropped somewhere in the U.S. to test it.

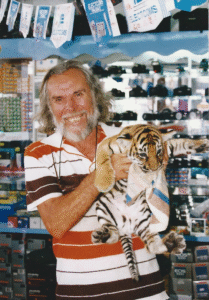

My most vivid memory, though, is of my grandmother’s brother — Uncle Nikita, who lived in Moscow. As a child, I was convinced he was a pirate. His apartment was filled with glass jars holding fangs and claws of strange animals, figurines from exotic places, and photographs from his travels. Of course, he wasn’t a pirate.

He was a circus performer — a trainer of wild beasts. He had toured many countries, and perhaps that’s why his home felt like a cave of treasures.

He loved talking about Italy — especially Naples. When I finally found myself there in 2023, wandering its narrow streets, I thought of his stories and tried to imagine him walking the same streets fifty years earlier, when tourism wasn’t yet a mass phenomenon.

That’s when I realized: all of it — the objects, the memories, the people who made and carried them — is a single thread. And maybe it all began with that small wooden figurine of a Tajik woman.

A tiny piece of carved wood that once taught me how to see the soul inside things.